The five-star admirals who won the war in the Pacific

They were children of the Victorian Era. Annapolis graduates around the turn of the twentieth century. Junior officers in World War I, captains by 1927. They gained their first admiral’s stars by the 1930s, and all four were near or past retirement age when war broke out. Yet they rose to the pinnacle of leadership in that war and played outsized roles in the Allied victory. And one by one, as their talents became unmistakably clear, they each received a fifth star, becoming the only five-star admirals in American history. Walter Borneman engagingly tells their stories in his joint biography, The Admirals.

The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy, and King — The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea by Walter R. Borneman (2012) 522 pages @@@@ (4 out of 5)

The four five-star admirals

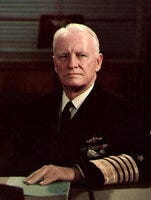

Chester Nimitz

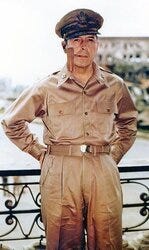

Chester W. Nimitz (1885–1966) was Commander-in-Chief of the US Pacific Fleet and led all Allied air, land, and sea forces in the Pacific Ocean during World War II. (General Douglas MacArthur commanded American forces in the Southwest Pacific, a second operational area.) Nimitz was the US Navy’s leading authority on submarines, and in World War I, he pioneered the new technique of refueling ships at sea, which proved to be crucial in the later war in the Pacific. Nimitz was even-tempered and rarely overruled subordinates. His personal visits to sailors and soldiers in the field consistently boosted morale. After the war, he served briefly as Chief of Naval Operations and then moved to Berkeley, California, where he and his wife lived from 1947 to 1964.

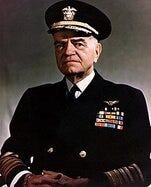

Bill Halsey

William (Bill) Halsey Jr. (1882–1959) commanded the United States Third Fleet in the South Pacific. He was one of the US Navy’s most aggressive and successful leaders at sea and became far better known to the American public than his superior, Chester Nimitz. He led allied forces during the Battle for Guadalcanal (1942–43) and played a leading role in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, considered by some military historians to be the largest naval battle in world history. Because of controversy surrounding some of his decisions during the war, he was the last of the four five-star admirals to gain that rank — more than a year after Japan’s surrender.

Bill Leahy

William D. Leahy (1875–1959), the least well-known of the nine five-star military leaders, met then-Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War I. The two became friends, and in 1942 Roosevelt recalled him to active duty as his personal Chief of Staff. He served in that position throughout the war and was at FDR’s side at many of the nine Allied war conferences where the President met with Winston Churchill and other British and Allied leaders.

Leahy was also the de facto Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff both in Washington DC and in joint meetings with the British military. Late in the war, as Roosevelt’s congestive heart failure limited his work day to four hours or less, Leahy, already the equivalent of national security adviser as well as chief of staff and the nation’s most senior military officer, increasingly spoke for the President himself.

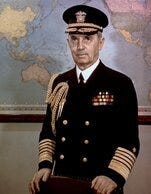

Ernest King

Ernest King (1878–1956) “may have been the most overlooked strategist of the Allied planning councils.” He commanded the US Navy during World War II and was a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. After William Leahy, he was the most senior naval officer in the war. Like Leahy, he served from his post in Washington, DC. King was notoriously short-tempered and intolerant of those he deemed intellectually inferior. Like a great many other naval officers, he was contemptuous of Douglas MacArthur and often found himself at odds with the army over the general’s self-promoting proposals. However, he worked effectively with Army Chief of Staff George Marshall.

The army’s five counterparts to the four five-star admirals were (in the order they were named) George C. Marshall, Douglas MacArthur, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Henry H. (“Hap”) Arnold, and, much later, Omar Bradley.

The Big Picture in 1942

When Chester Nimitz took command in the Pacific as CINCPAC (Commander in Chief, Pacific) in January 1942, most of his fleet lay on the bottom of the ocean. Japanese forces were running rampant throughout the vast region, and a lesser man might have quailed at the challenge. Yet despite continuing Japanese advances, the United States Navy went on the offensive almost immediately, with morale-building “nuisance raids” at Kwajalein and Marcus Island (both in February 1942), Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle‘s PR-motivated bombing of Tokyo (April 18, 1942), and the Battle of the Coral Sea (May 4–8, 1942), where the Americans stopped the Japanese advance in the South Pacific.

Within six months of Pearl Harbor, Nimitz’s forces already began to turn the tide with a brilliant victory at the Battle of Midway (June 4–7, 1942). There, the admiral adroitly made use of intelligence findings that enabled the US Navy to ambush a top-secret Japanese advance on Midway.

America had long prepared for war

In hindsight, none of this is a surprise. Since his first year in the White House, President Franklin Roosevelt had been steadily building the military capacity of the United States despite intense isolationist pressures. Long before Pearl Harbor, American shipyards laid the keels of a new generation of warships, budgets for the Army and Navy were greatly increased, the Selective Service Act of 1940 was signed into war, the scientific community began to mobilize, and the foundation was established to ramp up industrial production to meet the exigencies of a vast new war. When Japan struck on December 7, 1941, the United States wasn’t ready to strike back — but it would be very soon. And the leadership shown by the four five-star admirals ensured the US response would be powerful and effective.

In fact, “during the 1,366 days between December 7, 1941, and September 2, 1945 . . . the fleet grew from 790 vessels to 6,768, and its complement of officers, sailors, and marines swelled from 383,150 to 3,405,525.” At the outset, the US Navy in the Pacific boasted just three aircraft carriers. By the end of the war, there were 21 fleet carriers and 70 escort carriers, and the American Navy dwarfed every other nation’s forces on the seas.

For the United States, the war in 1942 was mostly in the Pacific

Despite Roosevelt and Churchill’s agreement at the Arcadia Conference (December 22, 1941-January 14, 1942) on a “Germany First” strategy, the American effort in the war during that first year largely took place in the Pacific. US troops didn’t actively engage the Axis elsewhere before November 1942, when Dwight Eisenhower launched the Allied invasion of North Africa.

The Pearl Harbor attack was a strategic failure

Japanese Admiral Chuichi Nagumo‘s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor had failed as a strategic effort, and his boss, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the plan, knew it. He was perfectly well aware that Nagumo’s failure spelled defeat for the Japanese Empire after what would clearly become a long war. Nagumo’s planes had failed to destroy the strategically important oil storage tanks on Oahu, which contained 4.5 million barrels of fuel oil. The attack had also left nearly intact the dry docks, maintenance facilities, and submarine base.

Japanese forces were spread thin

From the outset, the Japanese Empire spread its forces dangerously thin over an area that covered an enormous slice of the Earth’s surface. Since 1937, Japan already had millions of soldiers on the Chinese mainland, where none of its leaders’ hopes for a quick victory had panned out. Elsewhere, its forces sprawled from Singapore, Malaysia, and Taiwan to the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), the Philippines, and hundreds of small islands scattered throughout the Pacific. It was hubris to imagine that the Empire could successfully defend it all against the gathering might of the world’s biggest industrial power.

American strategy was set early in the war and followed consistently throughout

Ernest King’s operational orders to Nimitz were “to secure and hold the communication and supply lines between Midway, Hawaii, and the West Coast” and, second, “maintain a similar lifeline between the West Coast and Australia.” Those orders governed the Navy’s strategy in the Pacific throughout 1942 and beyond. Despite a raging debate over whether to move against the Philippines or Taiwan — a debate MacArthur won — US forces held that line in 1942 and steadily moved west and north from it on the way to Tokyo during the following three years. The strategy couldn’t have been clearer.

It’s difficult to escape the impression that, as challenging, bloody, and costly as were those three succeeding years, the die was truly cast for Allied victory in the Pacific by the end of 1942. Midway was, indeed, the turning point — and the four five-star admirals had a great deal to do with making it that.

Leahy and King’s unique roles in the war

For two of the five-star admirals, Leahy and King, the war was global. While Nimitz, Halsey, and their colleagues prosecuted the war on the Pacific, Leahy and King held strategically central positions in the American hierarchy and became deeply involved in the European war as well.

William Leahy

As FDR’s chief of staff and personal representative, William Leahy chaired meetings of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, mediating between Ernest King and George Marshall. The two men managed to work together after initial friction, but they communicated almost exclusively by memo even though the buildings in which their offices were located stood side by side. (The fourth member of the Joint Chiefs was General Henry H. (“Hap”) Arnold of the Army Air Force, but he answered to Marshall and was not an equal.)

Internationally, on the numerous occasions when the Joint Chiefs met face-to-face with their British counterparts, Leahy chaired that body, too. (It was also known as the Joint Chiefs of Staff.) There, his role often boiled down to minimizing the conflict between Sir Alan Brooke, chief of the Imperial General Staff, and General Marshall, which frequently grew contentious. He also took it upon himself to increase the flow of resources to Nimitz in the Pacific and to work around Winston Churchill’s obsessive interest in directing the Allied attack toward the Eastern Mediterranean. It was largely Leahy’s patient diplomacy which ensured that the Prime Minister didn’t divert resources from the impending invasion of France.

Ernest King

Admiral King was the Navy’s most senior leader during the war and thus was forced to devote much of his time and energy to monitoring and supporting Admiral Nimitz in the Pacific. At meetings with the British, he fought fiercely for increased support for Nimitz and managed to increase the allocation of resources from fifteen percent of the overall effort to thirty percent. However, his role in Washington was global. He had parallel responsibility for naval operations in the Atlantic, where he was credited with providing crucial support to the British struggle against the Nazi U-boats that threatened to starve the British people. And, like Leahy, he assisted in the American push to move ahead with the Normandy Invasion against British opposition.

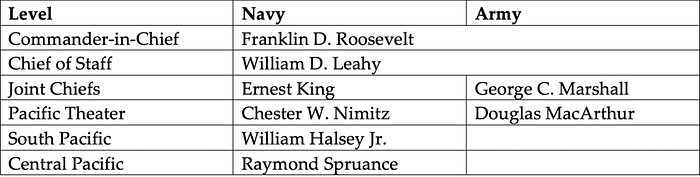

Who reported to whom

The interactions among the four five-star admirals and the many other naval officers and government officials they dealt with in the war can be hugely confusing. And that’s compounded by the fact that, even though all four men reached the exalted rank of five-star Fleet Admiral, they were at different levels in the wartime hierarchy. Here, then, is a stylized and oversimplified organization chart to help clarify the respective roles of The Admirals‘ principal players in the Pacific war.

Assessing Douglas MacArthur

With the hindsight of seven decades, it’s tough not to conclude that Nimitz’s counterpart in the Army, General Douglas MacArthur, was more trouble than he was worth. And Walter Borneman makes that clear in The Admirals. Had another general been in charge in the Philippines in December 1941, he would surely have been relieved of his command for dereliction of duty. Unaccountably, although he knew war was coming — and had nine hours’ warning after the attack on Pearl Harbor — MacArthur left his airplanes sitting wingtip-to-wingtip on the tarmac, where they were destroyed by the Japanese. Then, in another misguided move, he marched all his troops onto the Bataan Peninsula, where they were vulnerable to Japanese attack. But MacArthur was a legend, and America needed a hero.

Although MacArthur performed admirably for the most part as American “proconsul” in Japan, he showed his true colors a few years later when he took command of United Nations forces in Korea. Once he started threatening to drop atomic bombs in China along the Yalu, President Truman finally fired him on April 11, 1951.

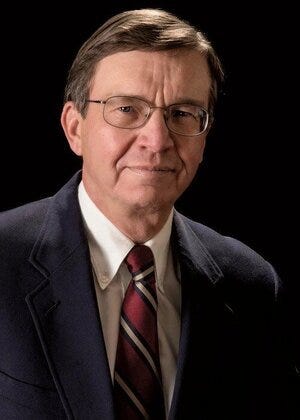

About the author

Walter R. Borneman (born 1952) is the author of five popular books about American history in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. The Admirals won the Samuel Eliot Morison Award for Naval Literature. He lives in Colorado, where he has practiced law. He is also well known as a mountaineer.

For additional reading

You might also be interested in:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II (plus many runners-up)

- The 10 best novels about World War II (with 30+ runners-up)

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page of Mal Warwick on Books.